Canada has one of the highest education rates in the world. Despite this, one in six Canadians struggle with everyday reading and writing. This statistic climbs higher still when you examine literacy rates inside Canadian penitentiaries.

According to a fact sheet by The Literacy and Policing Project, 79 per cent of offenders entering Canadian correctional facilities don’t have their high school diploma. In fact, inmates are three times as likely as the rest of the population to have low literacy skills, and while low literacy does not necessarily cause someone to commit crimes, people with low literacy skills often find themselves frustrated and dissatisfied with their daily lives. They also struggle with problem-solving and critical thinking. The inability to read and write also makes it difficult for inmates to access support programs while inside that would help improve their lives post-release.

Since this growing literacy gap first came onto the Correctional Service of Canada (CSC)’s radar in the late 1980s, the federal government has been working with community partners on programs geared toward increasing literacy rates in Canadian correctional facilities. Improved literacy reduces an inmate’s chance of re-offending by up to 30 per cent, according to The Literacy and Policing Project. Newly released inmates with a firm grasp on basic reading and writing also have a higher chance of finding employment, which further reduces their odds of re-offending.

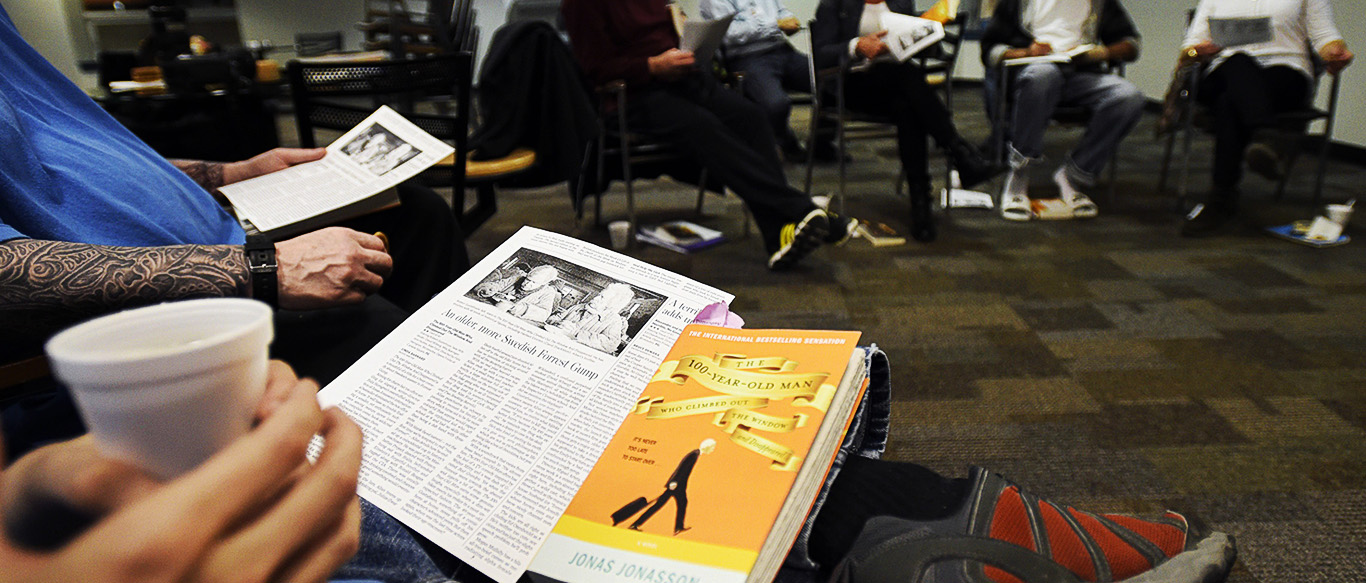

That’s where Book Clubs for Inmates (BCFI) comes in. BCFI is a non-profit registered charity that organizes volunteer-led book clubs within federal correctional facilities across Canada, from British Columbia to Nova Scotia.

Book Clubs for Inmates Executive Director Tom Best

According to BCFI’s Executive Director Tom Best, literacy can profoundly affect an inmate’s life, both while inside and outside of prison. Books can expand one’s horizons in dramatic and unexpected ways, especially when it comes to building empathy. And that, he says, is an important skill to have inside a prison.

“Book clubs help you feel like you’re part of a community,” says Best. “It’s not just about building empathy, but also the direction and purpose reading gives in a way few other things can. By discussing books as a community and exposing yourself to other viewpoints in an open forum, it gives people an opening to talk about other issues and feelings that can be evoked by what they’re reading.”

BCFI was founded in 2008 by Rev. Dr. Carol Finlay, when she visited Collins Bay Institution in Kingston, ON. Although she was originally there under a Ministerial capacity, she was surprised when her suggestion to start a monthly book club was welcomed with enthusiasm. After the book club’s success at Collins Bay, the program was expanded in 2010 to other Ontario institutions. The first book club outside of Ontario was held in June 2013 at Stony Mountain Institution in Winnipeg, MB.

Today, BCFI runs French and English language book clubs for men and women incarcerated in minimum, medium, and maximum security facilities on a national level. Best stepped into the role as Executive Director in January 2022.

Book Clubs for Inmates Founder Rev. Dr. Carol Finlay

“Carol saw a need for a fellowship–to bring together people from all parts of the inmate community without judgment, to use book clubs as not only a cathartic way of processing their lives in and out of prison, but also as a way to transport themselves outside the walls of the prison,” Best says. “I’m filling in very big footsteps. She deserves all the credit. My ideas and accomplishments pale in comparison to the work she has put in.”

Pre-COVID, there were around 600 inmates participating in the program across Canada every year. The pandemic, predictably, has affected their operations, but Best says BCFI plans to expand significantly in the coming months and years as they adjust to the ‘new normal.’ He also hopes his connections and knowledge of the book industry will help catapult BCFI to a new level.

“The big thing for me is the opportunity to make books accessible,” he explains. “I’ve been very blessed. I’m the son of one of the most prominent printers in the country at one point, so I’ve always had that love affair with books. I spent about 30 years in the book business, I did a number of senior jobs in the publishing industry. The book industry is always in flux, and Carol was sort of stymied by that, so I thought that might be where I could help.”

In the days ahead, BCFI plans on improving their library through Best’s connections to the book industry, and seeking more funding to continue expanding their book club programs. Best says they have plans to set up a system with CSC that will allow “a huge influx” of new fiction and non-fiction books into prison libraries across the country, both in English and French. He says improving accessibility to books is an immediate priority to BCFI, because of the practical essential skills inmates can gain from reading.

And although Rev. Dr. Finlay has stepped back to allow Best to take on a more senior role, Best says he both welcomes and relies on her continued participation with BCFI… Especially when it comes to book selection. “Carol will always be our Founder,” he says. “We have a variety of eclectic readers in our book clubs, and she really has her thumb on what will appeal to the inmates. Her experience and background is invaluable to this enterprise.”

Another program BCFI plans on expanding in the near future is ‘ChIRP,’ or the Children of Inmates Reading Program. ChIRP is led by facilitator Carla Veitch, and the program has really taken off. ChIRP aims to nurture and enhance relationships between inmates and their children through reading, by allowing inmates to record themselves reading a children’s book of their choice. The recording is then mailed to the inmate’s families for their children to keep.

“The great side of this is that it does help in terms of opening lines of communication between parent and child,” Best explains. “For the kids, it indicates to them that their parent cares about them. It shows that even if they can’t be there in person, they’re still taking the time to get involved in their children’s lives.”

“The great side of this is that it does help in terms of opening lines of communication between parent and child,” Best explains. “For the kids, it indicates to them that their parent cares about them. It shows that even if they can’t be there in person, they’re still taking the time to get involved in their children’s lives.”

Best says the opportunity of being read to, in general, is fundamental to a child. But unfortunately not all children are afforded this opportunity, especially if the parent’s own parents did not read to them as children. This is something, according to Best, that people who have had that privilege often take for granted.

“For some inmates who may not have had that opportunity growing up, they can now offer that to their own kids,” he says. “Some of them even do crazy voices for the characters. It’s something those kids will be able to hold onto forever. Hearing your own parent’s voice is beneficial at any time, especially when you can’t be physically together.”

Currently, ChIRP is offered in Collin’s Bay Institution and Beaver Creek Institution in Ontario, Drumheller Institution in Alberta and Springhill Institution in Nova Scotia. But BCFI plans on eventually expanding the program to a national level, and are hoping to get their hands on some large-scale funding to double it in size over the first year alone. They also hope to digitize the recordings, so they can be sent online rather than through the mail.

BCFI is almost entirely run by volunteers, from the program facilitators and directors to the volunteer readers. Best says many of their volunteers come from inside the facilities themselves, such as library staff and even Correctional Officers.

“Engaging with the inmates on such an intimate level gets [the staff] more actively engaged with the inmates, their lives and their feelings,” Best says. “It builds relationships and empathy between staff and inmates outside of book club, as well.”

He explains that engaging regularly with book clubs help inmates who are nearing release to acclimatize, with more general knowledge of what’s going on outside. He reiterates that it can also greatly improve an inmate’s odds of finding a job after they are released, by arming them with basic language skills and improved emotional intelligence.

He explains that engaging regularly with book clubs help inmates who are nearing release to acclimatize, with more general knowledge of what’s going on outside. He reiterates that it can also greatly improve an inmate’s odds of finding a job after they are released, by arming them with basic language skills and improved emotional intelligence.

“In the long term, it helps inmates become better citizens,” Best says. “And in turn, it helps the staff relate more and connect better with the inmates. It’s surprising what horizons reading can open up.”

Although volunteering with BCFI is popular among correctional staff, anyone can be a volunteer reader. Best says they are not necessarily looking for academics, all that is required is a passion for books and reading, an interest in leading discussions and most importantly, active listening skills.

“Being a good listener is a huge asset,” says Best. “The important thing is to guide the conversation, not dominate it. You also need to be prepared to accept that not all books are going to be well-received, and be prepared to discuss that. Those conversations have value just as much as the positive ones… sometimes even more so.”

To find out how you can get involved with Book Clubs for Inmates, visit the volunteer portal on their website.

*****

Photos used with permission from Book Clubs for Inmates.

Victoria St. Michael is a multimedia content creator with experience producing high-quality print and digital content. Victoria graduated with an Honours Degree in Digital Journalism from the University of Ottawa and a Journalism Diploma from Algonquin College, and has bylines in publications across North America. With an avid interest in humanitarian and global issues, she hopes to use her unique voice to help build a well-informed, forward thinking and progressive Canada.