In a turbulent time when many would assume that students would be shying away from joining the police force, Tennant says that she is more motivated than ever to join the community policing efforts in her area after graduation.

“Police are the first point of contact for people experiencing a mental health crisis, who are being victimized or who are putting others at risk and I want to be the one to help,” says Tennant. “With everything that has gone on, I want to be the person who commits to doing better.”

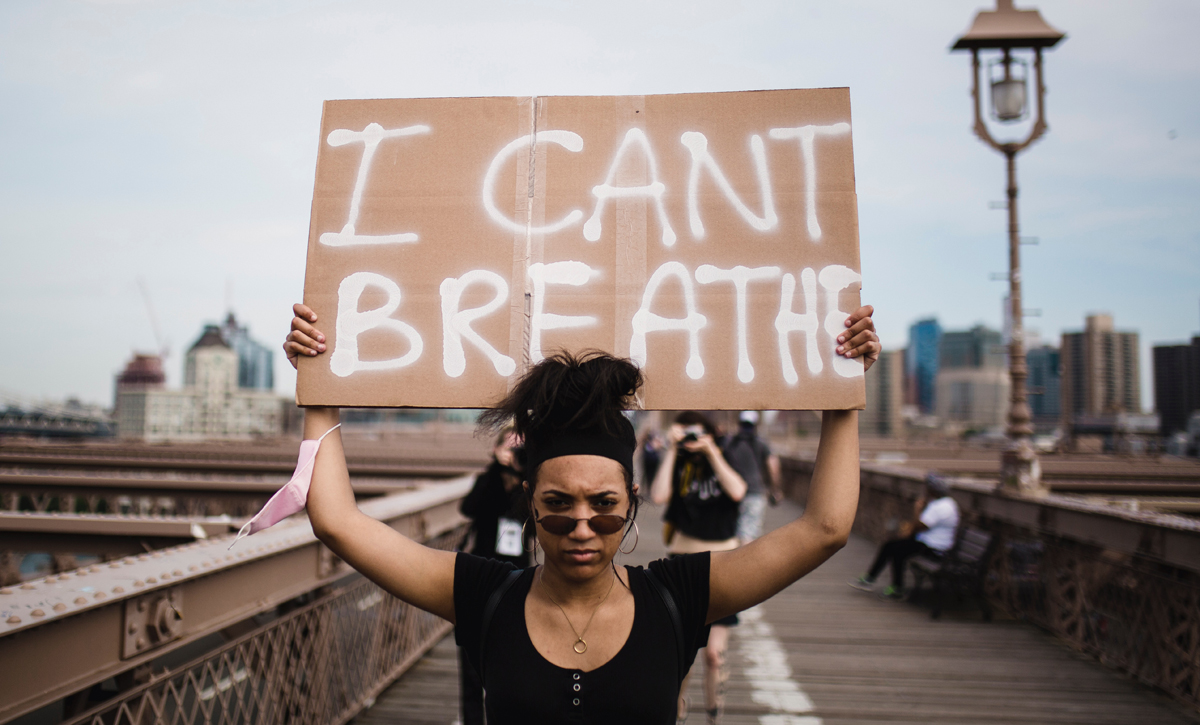

After the murder of George Floyd by former Minneapolis police officers sparked nationwide protests across the U.S. in 2020, the law enforcement community has been awash with criticism and accusations of ongoing systemic racism and police brutality.

Police in Canada were not immune to the backlash. The deaths of Abdirahman Abdi, Eishia Hudson, Stewart Kevin Andrews, Regis Korchinski-Paquet and other Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPOC) at the hands of Canadian police officers have flared emotions right in our own back yard.

In November 2019, the Globe and Mail reported that between 2007 and 2017, more than a third of people killed in shootings by the RCMP were Indigenous. A 2018 study by the Ontario Human Rights Commission also found that Black residents are 20 times more likely to be involved in police shootings than white people in Toronto.

“The racial injustices being brought to light is the first step in rectifying the problem,” says Tennant. “Police need to be part of the solution. They need to use their authority and discretion in a fair and impartial manner, as well as work to build more positive relationships with Indigenous and other marginalized communities.”

Shakil Choudhury, a Toronto-based consultant who has more than 25 years of diversity training experience with police forces in Ontario and Alberta, agrees that systemic racism is pervasive in policing and the Canadian justice system. He says that although police organizations are becoming more aware, many still refuse to see racism as a systemic pattern, which is impeding any significant progress.

“It wasn’t that long ago that police even started to admit that racial profiling was a thing,” says Choudhury. “They say ‘we don’t agree with the term systemic racism,’ but the issue is that they’re completely misunderstanding the problem. Have they become more aware? Yes. But have things gotten better? Not really. If change has happened, it would be in small pockets.”

Choudhury attributes the systemic racism problem to a long-enduring culture within policing that has normalized toxic behaviour. He says that the “good guy, bad guy” attitude so prevalent in policing needs to be eliminated, replacing the punitive mentality that has seeped into the public’s perception of police with genuine support.

Choudhury adds that the oft-blamed “bad apples” within policing do exist, just like they would in any other profession, but that the problem is actually embedded within every part of the policing system, from the leaders up top to Human Resources departments to the officers out on the streets.

“It’s about pattern recognition,” Choudhury reminds us. “Only when you become aware of toxic patterns can you do something about it. If a leader of a police organization, or the officers, are not even aware that it’s happening, they’re going to dismiss it. They’re not going to see the pattern that’s at play.”

Tennant says that since the Black Lives Matter movement began gaining renewed traction in Canada, the curriculum in her program has adapted to include discussions on systemic racism and police brutality toward BIPOC.

“We’ve had group discussions in class and watched videos that have gone viral – most of which, I am ashamed to say have been about local police in my area,” says Tennant. “We discussed what we heard the officers say to the accused and if they tried to de-escalate the situation before using physical force.”

PoliceTestPrep.ca names St. Lawrence College as one of the Top 10 Police Foundations programs in Canada. According to Leslie Casson, the associate dean of Justice Studies and Applied Arts at St. Lawrence, the college is in the process of launching an equity census and listening tour to gather data on important topics such as racism, bias-free policing, fairness and impartiality.

They are organizing a task force to carry out this initiative, and Casson says that recommendations will be made by April of this year.

“At the course level, individual professors are making efforts to address these issues with their students, which is a great start,” says Casson, “but this is still an individual rather than a program-wide response. The recommendations of the EDI task force will inform our efforts to address these issues more formally and comprehensively in the curriculum and as a college.”

Rather than perpetuating this long-standing pattern by continuing to dismiss the issue as ‘a few bad apples,’ educators across Canada are joining St. Lawrence College in shifting their operations toward solutions-based training and education.

“The events of the past year have only confirmed to us that we are on the correct path in constantly reviewing training and revising content,” says Steve Schnitzer, director of the Justice Institute of British Columbia (JIBC) Police Academy in New Westminster. “We have always welcomed feedback to our training content and will be formalizing new processes to include increased consultation with community and diverse groups.”

JIBC is a post-secondary educational institution that trains professionals in the justice, public safety and social services fields. Their Police Academy delivers provincially approved basic training to all new municipal police recruits, as well as advanced training for police officers serving in municipal departments, the RCMP and other law enforcement agencies in the province.

In 2018, Schnitzer says the Province of B.C. funded a review of the JIBC Police Recruit Training Program, overseen by a steering committee of diverse organizations such as the B.C. Civil Liberties Association, PIVOT Legal Society and other community stakeholders. Several recommendations were made based on this review, and JIBC is now in the process of finalizing these changes.

Schnitzer adds that five of the recommendations being implemented at JIBC this year have direct linkages to the events of the past year, as well as a greater focus on Indigenous and vulnerable populations.

He also says that the key to addressing the way Canadian law enforcement is perceived is through ongoing and open dialogue between police organizations, students, educators, and the communities who are affected. Choudhury agrees, adding that listening projects such as these are a critical factor in the reconciliation that needs to occur in order to rebuild trust between police and the marginalized communities they serve.

“Until police leaders are willing to recognize the histories that they may not have created, but are still a part of, they won’t be able to properly reconcile these issues,” Choudhury says. “And many organizations aren’t willing yet to recognize their own roles in that.”

Schnitzer says the curriculum at JIBC is constantly being adapted and that several enhancements will be rolled out later in 2021, including an increased number of training simulations that involve vulnerable people and people in crisis.

“In this case, the role of police training institutions is to ensure that mechanisms and processes are in place – such as advisory committees – so that these conversations can happen and that feedback can be received and implemented,” he says. “Accountability and transparency are very important and having consultative frameworks in place leads to this occurring.”

Choudhury believes that in order to see progress in the immediate future, leaders in existing police departments must join students and educators in shifting their mindset to become what he calls system thinkers.

“Leaders need to be asking themselves, ‘I wonder if this is the canary in the coal mine. I wonder if this interaction is actually reflective of a bigger system problem,’” he explains. “Don’t treat an individual case as if it’s an exception. Police leaders need to be system thinkers, especially when it comes to issues of identity and how power works – and therefore how privilege works. What communities are being over-policed? What are the consequences of that, and are they disproportionate?”

Meanwhile, Tennant says that students such as herself, as well as new officers, also have an integral role to play in ensuring that throughout their careers, Canadian policing communities will be left better than they found them.

“I think that educating ourselves on the issues that are happening now in our country and throughout Canadian history is important,” she says. “For example, for myself doing this has really changed my own perspective. Both Indigenous and Black people are vastly over-represented in Canadian prisons despite the small portion of the population they account for. I think that alone proves that systemic racism exists in the Canadian justice system.”

“Indigenous people make up just a little more than four per cent of the general population but account for more than 30 per cent of the Canadian prison population,” Tennant continues. “They are more likely to serve time in maximum security and serve more time behind bars before getting out on parole than non-Indigenous inmates. I think that the justice system plays a huge role in this, but law enforcement officers need to understand the issues facing Indigenous people such as poverty, high rates of victimization, etc. are a result of centuries of injustices.”

Sadly, these stats check out, painting a picture of just one facet of the dark history of Canadian policing. A CTV News analysis published in June 2020 revealed that Indigenous people are 11 times more likely than non-Indigenous Canadians to be accused of homicide and are also 56 per cent more likely to be victims of crime.

According to Choudhury, in many cases, these biases among police officers are unconscious. However, he is quick to add that just because a bias is unconscious does not mean it should remain unaddressed, which reinforces the need for more effective diversity training in Canada.

“Here’s the thing,” he says. “Diversity, equity, inclusion, at the best of times, are highly emotional topics of discussion. It’s about our identities. It can be interpreted as whether we are good or bad individuals, and whether the group that we belong to is good or bad.

“It happens even more in the context of policing,” Choudhury adds, “Because unlike doctors and other professions, police officers have the ability to suspend civil liberties. And they have weapons, which comes with extra responsibility. Police officers are put under a huge amount of pressure, and as a result, if they know they’re going to be told how bad they are, who’s going to want to learn?”

Choudhury says that the most important thing for the policing community to immediately consider in order to address the issue of systemic racism is pure leadership, the implementation of more effective mental health resources within the workplace, and in-context training.

“We know from best practices in any context that you have to have senior leaders on board,” he says. “They have to be walking the walk and talking the talk. There needs to be constant vigilance, and constant data collection so we can accurately measure progress.

“Diversity and equity training should also be integrated with social and emotional intelligence training,” Choudhury continues. “It’s especially important in a context with such high emotionality, and where there’s so much scrutiny happening. Police officers themselves are in crisis situations every single day. So, they need to learn how to manage their own emotions.”

While policing students and educators seem willing to recognize the patterns at work and take dramatic action toward meaningful solutions, existing police departments also need to be ready to answer the call – and it all depends on senior leaders taking initiative and shifting their way of thinking toward the bigger picture.

While viral rallying calls among Black Lives Matter activists such as “defund the police” and “abolish the police” trigger alarm bells in the minds of many members of the policing community, Choudhury reminds us to consider what this really entails.

“I do think policing has to be reinvented,” says Choudhury. “What is their purpose, when can police be partnered with other services to provide a more comprehensive response, and when are police even the most appropriate First Responders to help with a situation? Why don’t we have teams of mental health professionals responding to some of these nonviolent calls?”

Choudhury says until police leaders can recognize that there is a massive problem with how policing has been done for a long time, there will be no way to formulate effective solutions. He adds that heeding these calls to dismantle and rebuild policing as we know it could also facilitate workplace harm reduction for police officers themselves.

“I think the calls to reimagine policing are a big one, and it’s not as scary as everyone seems to think it is,” he says. “In fact, I would even say it would be beneficial to officers themselves in easing some of that immense pressure they are facing. It’s a damn hard job, so how can we reinvent policing so that police officers don’t have to go through so much wear and tear?”

According to Schnitzer, from past experience, the first thing that is usually affected by budget cuts is training. “Police training is an important investment in the foundation of policing,” he says, “and with increased public demands, this is an area that should not be defunded.”

Tennant says that ultimately, she has no regrets about the career she chose to pursue. If anything, the events of this past year have inspired Tennant to follow a path she never would have considered before. She says she is proud to have the chance to be part of creating a brighter future for Canadian law enforcement and to help rebuild mutual trust and respect between police and the marginalized communities they have pledged to protect.

“I think that by being a voice within the force, not separating myself from the general population and the problems within it and doing my best to be fair and just with my discretionary power and position of authority, I can become part of the solution.”

Victoria St. Michael is a multimedia content creator with experience producing high-quality print and digital content. Victoria graduated with an Honours Degree in Digital Journalism from the University of Ottawa and a Journalism Diploma from Algonquin College, and has bylines in publications across North America. With an avid interest in humanitarian and global issues, she hopes to use her unique voice to help build a well-informed, forward thinking and progressive Canada.